Golfer's elbow

Golfer’s elbow is also known as medial epicondylitis. It is a painful condition that affects the inside of the elbow. Some people also report weakness in the hand or wrist. It usually starts gradually and gets worse with increased use through repetitive actions like striking a golf ball.

It is not very clear what causes golfer's elbow, although repetitive activities such as striking a golf ball, shovelling, or hitting a nail can contribute. Swimmers can also develop it when pulling their arm through the water. It is thought that small tears occur within the tendons that attach to the outside of the elbow and control finger and wrist movement. This explains why it is activities that place strain on these muscles and tendons which exacerbates the pain and why rest is so important.

The main symptom is pain on the inside of the elbow. There is usually a tender point that can be felt. The pain tends to settle with rest and comes on with activities, particularly repetitive activities.

The mainstay of treatment is rest and avoiding those activities which exacerbate the symptoms. If you are able to rest, it may settle down within a couple of months. Anti-inflammatory medicines may also be helpful. If this is not enough then special physiotherapy and a brace on your forearm can be effective.

In some cases an injection (either a plasma rich protein (PRP) injection or a steroid injection) at the site of pain can be useful. While it may only provide temporary relief, some people, particularly if combined with rest from the inciting activity, can get longer lasting effects.

In a minority of cases resistant to other treatment, surgery may be required.

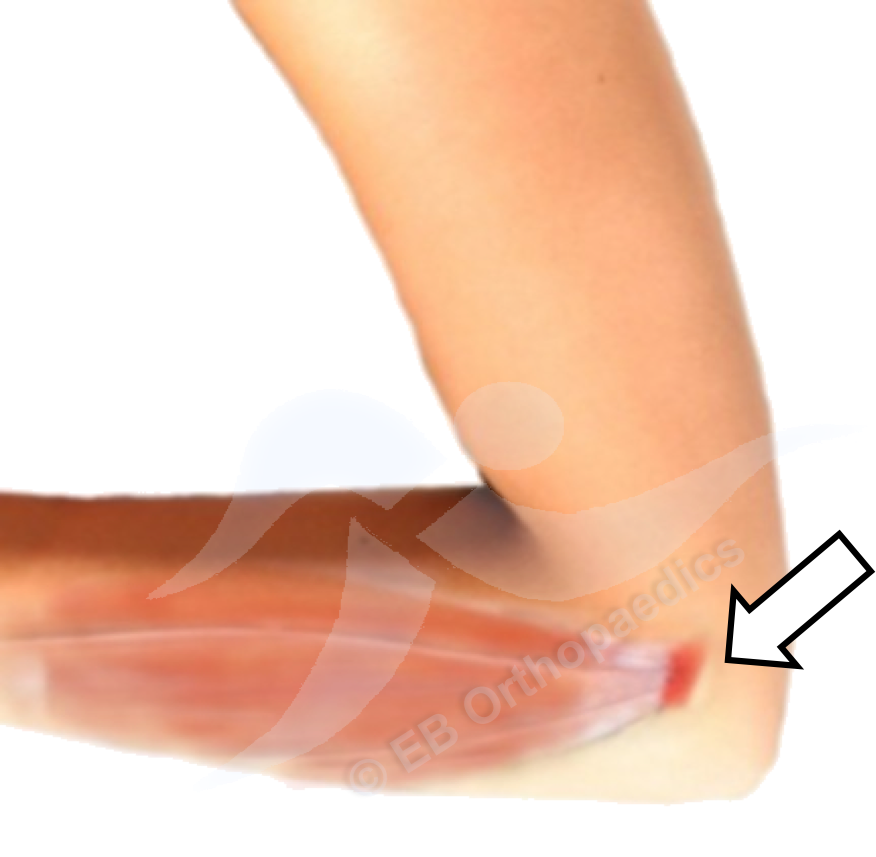

There are different approaches to surgery for golfer’s elbow but they generally involve an incision on the inner aspect of the elbow and removing the abnormal tissue from the tendons, together with any bony prominence.

The surgery typically involves a general anaesthetic and is done as a daycase procedure.

After surgery, exercises are started straight away and progressed under the guidance of a physiotherapist. The main movements to avoid are those which caused the initial problem, as well as any sudden jerking movements.

Results of non-surgical treatment are very good and the majority of peoples’ symptoms settle with time.

For the few people who need surgery, they usually have a good result, provided the rehabilitation advice is followed. Symptoms however can still recur, particularly if returning to an activity that caused the problem initially.